Reimagining the Coronation of 1953

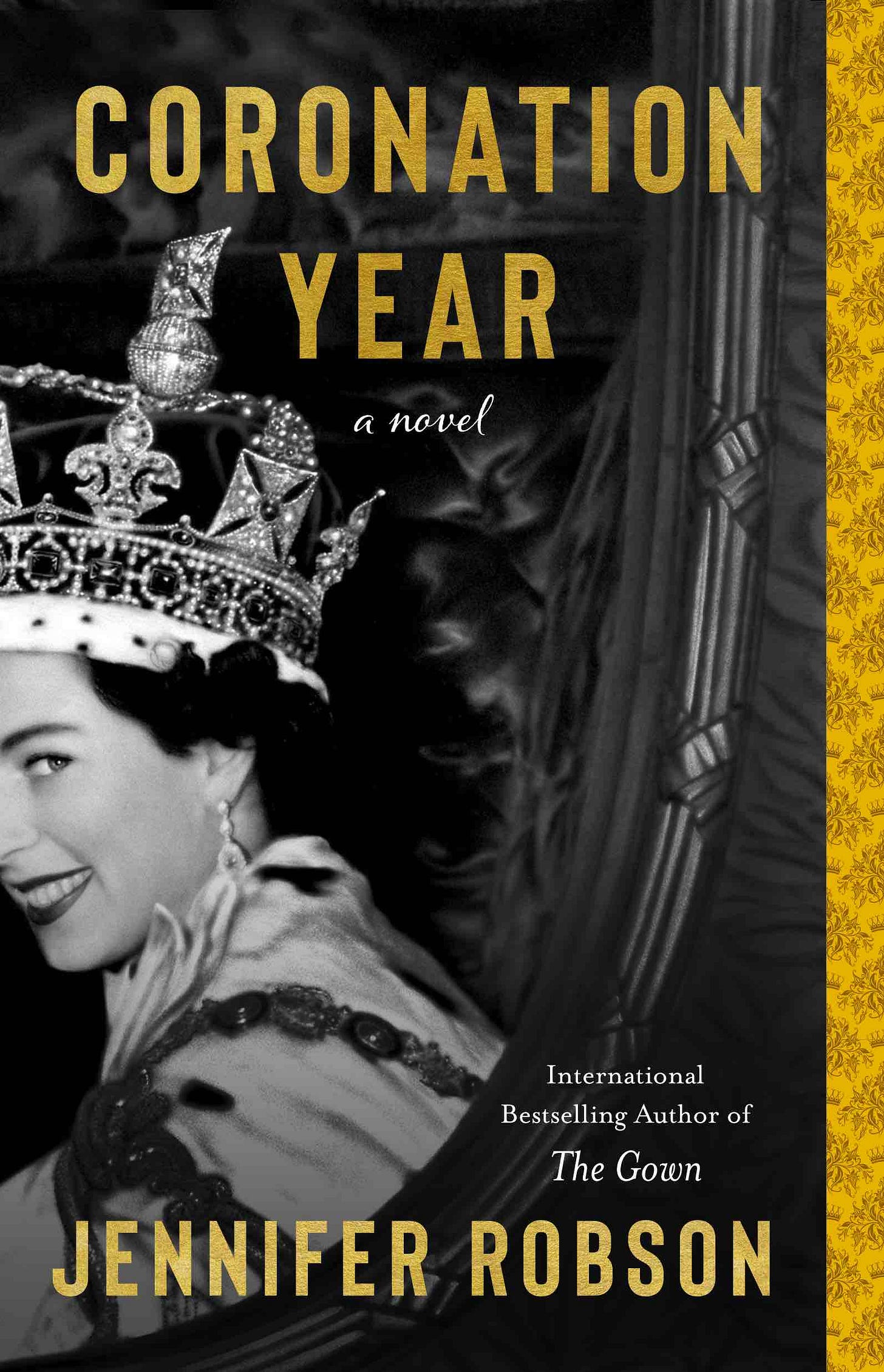

Jennifer Robson, best-selling author of ‘The Gown,’ takes a new look at the run-up to Queen Elizabeth II’s crowning in ‘Coronation Year.’

This week, with less than a month to go until the coronation, the royal family has released new details about the pair of processions on May 6. King Charles III and Queen Camilla will first make their way from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey in the Diamond Jubilee Coach and then leave, newly crowned, in the Gold State Coach. The route in both directions will stretch down the Mall, through Admiralty Arch and Trafalgar Square then along Parliament Street to Westminster Abbey.

What will it feel like to watch the coronation procession? For clues, we can turn back the clock to Queen Elizabeth II’s own such journey in 1953. And I’ve got just the book to help with that! It’s called Coronation Year by Jennifer Robson. I know so many of you have read — and loved — The Gown, Robson’s fictionalized take on the seamstresses who made then-Princess Elizabeth’s wedding dress. Now Robson is back with her seventh historical novel, the second with a decidedly royal bent.

Coronation Year, which hit bookstores last week, looks at Queen Elizabeth II’s crowning through the eyes of three members of the crowd. There is Edie, the owner of a hotel on the procession route, as well as two guests who have come to document the coronation: Stella, a photographer, and James, a war hero and artist.

History “really animates me,” Robson said when we talked recently. “And I really, really wanted to know: What was it like to stand in the streets of London on the second of June 1953 and watch the queen go by in her Gold State Coach?”

Robson answers her own question with impeccable credentials and impressive research. Having received her doctorate in British economic and social history from the University of Oxford, she describes herself as “an academic by background, a former editor by profession, and a lifelong history nerd.” For both The Gown and now Coronation Year, she immersed herself in the time period through primary sources, including newspaper clips and recorded oral histories. You can sense the depth of Robson’s research in her writing, through the richness of the story she imagines and the complexity of her characters.

My conversation with Robson, just before the release of Coronation Year, stretched for nearly two hours. It was such a delight to hear her explain her writing process, including why she uses the royal family as a backdrop instead of as main characters and the tools she turns to to place herself in this period in history (there was an epic map for Coronation Year). Make sure you read to the end for her conflicted feelings on Charles’s coronation as well as her reflections on when her writing career took off. I hope you enjoy my chat with Robson as much as I did.

Reimagining the Coronation of 1953

Please note: Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Hello! I am thrilled to talk with you, Jennifer. You’ve written seven novels now, all of which are set around the two world wars. I’m curious where and how your interest in this time period intersects with your interest in the British Royal Family?

Jennifer Robson: In some ways, it’s two separate things. I’ve always had an interest in the royal family. I’m Canadian. The late queen and now the king are the head of state in Canada, they’re on our money. It’s embedded into Canadian society in a way that I think some people don’t necessarily expect.

I have very distinct memories of watching the royal wedding [of Charles and Diana] in 1981. Hilariously, I thought the Princess of Wales’s wedding dress was the most beautiful confection I had ever seen. I remember my mother groaning when Diana got out of the beautiful glass coach. The mountains of silk taffeta did not hold up well to being crammed into that quite small coach with her quite large father. I think my mom said, “She looks like she just pulled it out of the laundry basket.” All that said, I was enthralled.

As an adult, whenever there’s a royal occasion, I am up at the crack of dawn with my closest friends. I did it for the royal weddings and had a tea party for the queen’s Jubilee last summer. But I watched her funeral by myself and wept the whole time. I have a deep fondness for the queen and for that generation, too. I think that’s where it ties in. It’s the generation of my grandparents and the generation before that who lived through the Great War. It’s a period of such fascination for me, and a fascinating backdrop.

Backdrop is such an appropriate word, because I noticed how you use the royal family almost as a backdrop in both The Gown and Coronation Year. The books are set in this time, around these major royal events, but the Windsors are not main characters.

I’m interested in ordinary people and how great events affect their lives. Specifically I’m interested in women’s history and how the lives of women have changed particularly over the last century.

Would people necessarily be interested in just the very prosaic lives of ordinary people? It’s a harder sell. But if you then set that against the backdrop of this glittering spectacle of the royal wedding of ’47 and the coronation of ’53, then you start getting some dramatic tension and that’s something to build from.

I think that the contrast between ordinary people and the lives of the royal family is inherently fascinating.

And especially with the coronation, my fascination only grows and grows with each passing day. This is a ceremony that, in its particulars, is effectively a thousand years old. And how many things in this kind of disposable, everything-changes-in-a-heartbeat, nothing-seems-permanent society of ours, how many things do we encounter that are a thousand years old that we can witness? Very few.

Where did the idea for Coronation Year come from?

I started with this idea of watching the coronation go by. Why would the person be standing where they are? What if they lived on the coronation route? Then I started looking at the maps of the coronation route. What are the buildings along there?

For the most part [in 1953], they’re these great public buildings, along Whitehall and the Mall. Then you get into that part of the procession through Oxford Street, the shopping district and so on. There aren’t a lot of homes. You were unlikely to be standing in front of the place you lived.

So I thought: Well, where else do people live? Hotels! Oh, that’s wonderful. Hotels are catnip to writers. And then the story built up from there.

Where did you begin the research process?

There was one map in particular from Picture Post. Each week, in the centerfold of the magazine where you could detach it, they would have a double-page spread of an extraordinarily detailed map of the coronation route. The idea was that you’d save them and assemble them on your wall.

I had access to the digital files, so I printed out full-size copies. They took up this huge spot on my wall. You get a real sense of what the neighborhoods look like. I dug in and I thought: Where on the route will this imaginary hotel be?

I was going through this thing with a magnifying glass and then going onto Google Maps and then Google Street View to walk around. There is another website that the National Library of Scotland maintains that layers maps. You can see a contemporary map and then there’s a slider that you pull across and it fades to the map superimposed in exactly the same kind of axis of what a street looked like in, say, 1950. I could go back and forth to see how it’s changed and also see who the tenants are in the shops today and who the tenants were in the shops then.

Once you had your overarching idea, how did you develop your characters? Were you ever tempted to take on the point of view of the queen?

I had moments in writing Coronation Year where I thought, Do I take this back to [the atelier of designer Norman] Hartnell, where I set much of The Gown? Do I go behind the scenes at Buckingham Palace and adopt the point of view of one of [the queen’s] maids of honor?

I never contemplated writing anything from the point of view of Princess Elizabeth with The Gown or Queen Elizabeth in Coronation Year. Not because I find her in any way uninteresting. I have a deep reverence for the queen — and fondness for and interest in — but I never felt that I could fully capture her interior life.

Beyond that, I felt that there was something that made me hesitate. I thought: Okay, well, what if I try? What if I dig in there and go rummaging around and imagine who she is and put words in her brain? And there’s something about that that, again, for my purposes, didn’t feel right.

I’m not here to diss anybody else who has written a book with the queen as the central character. There’s some wonderful books out there.

And an entire television series that’s widely celebrated for that!

I think I’ve heard of it before! [Laughs] It’s just not where my personal comfort is.

When I’m creating my own characters, I can do anything to them. I’ve killed characters in the past and then I cry. I sit and cry like it’s somebody I actually knew. But I can construct kind of their psychological innards according to what I need for them in the book.

Coronation Year has three main characters. Without spoiling anything here, tell me who they are and a little bit about them.

One of my central characters is Edie, who owns the Blue Lion Hotel, which is on the coronation parade route. It’s a little hotel, it’s not very fashionable, it’s never been very fashionable, but somehow it has managed to stay reasonably solvent and open for almost 400 years. She’s been doing her best to keep it open and sees this moment, where the queen’s coach will pass by her hotel and she will be able to charge an absolute premium for hotel rooms. That did happen. People were paying hundreds and hundreds of pounds, which was a lot of money then, to see the queen pass by.

Then we meet Stella, who was a character in one of my previous books. Stella is a Holocaust survivor in her very early twenties. Her parents were killed during the war. They had run a small business writing tourist guides for various European cities. Stella is at a crossroads, working at a bookstore in Rome. She happens to see an advertisement for a photographer and miraculously she’s offered a position at Picture Weekly. She goes to London and stays as a paying guest at the Blue Lion.

The third character is James. He’s Scottish, but he comes from a mixed race background. His mother is Indian, his parents met when they were at Oxford. He was raised in Edinburgh. He felt acutely the othering and the sting of racism as a child. He signed up, and was in active service, during the war as a bomb disposal officer. But he struggled in the post-war period to find his feet, as so many did. He’s also an artist, a very talented artist, and he’s just starting to make a name for himself. He was awarded a commission to paint a portrait of the queen in her gold coach as she passes by a particular building on the coronation route. And that building happens to be across the street from the Blue Lion, where he then decides to go and stay.

Let’s talk about pacing. The book is almost entirely about the anticipation of the coronation — the actual ceremony comes at the very end. To me, that felt as if it reflected the real-life experience of waiting for the process. I’ll never forget how long I stood at the Platinum Jubilee last year, waiting for the procession to pass by, and then how quickly it was over.

I start the book on the first of January when coronation year is beginning. I didn’t feel that it worked for the narrative structure’s intention to draw out the coronation so that the actual ceremony takes up a quarter of the book or anything. I wanted it to appear in that moment almost in real-time. There’s an urgency, too, for the people who are there at Westminster Abbey to capture it for posterity.

As we near the first coronation many of us have ever witnessed, I’m curious what you think the role of the ceremony is in 2023? Is it needed?

The historian in me has a really clear answer for that, which is it’s the closest thing we can get to a time machine to connect us with the notion that the monarch not only has these powers invested in them but there’s also duties and sacred obligations. They are making oaths. It’s less that they’re taking power and more that they are accepting the role and then making very significant, binding promises effectively to do their best to uphold the law.

You can draw a direct connection between what will be happening on May 6 with the coronation of King Edgar in 973. That kind of blows me away. How many things do we see that are truly ancient, that have that kind of ineffable sense of timelessness? And this is one of those occasions. There’s a solidity to it that, for someone like myself [who was] brought up revere the queen and consider her my head of state, it’s very comforting. That’s my “in the for” column.

And in the “I feel anxious even talking about it” column is: Does this represent Britain and the Commonwealth as it is today? A country and a group of nations that are profoundly diverse, in which there are corrosive historic inequities that have still not been addressed properly? In which the ancestors, certainly not the current royal family, but the ancestors of the royal family had very pernicious connections? Is a coronation today appropriate?

It’s something that I find very uncomfortable even talking about — but that’s no reason not to talk about it. Is it inclusive enough? Because I think the way forward for the future for Britain and my country is that everyone belongs and everyone should be able to feel a part of these ancient ceremonies. And that task is all down to the king. I do believe that he wants to make this ceremony inclusive.

What changes do you expect to see in the coronation this time around?

It will be radically more inclusive. In 1953, there was a fuss over having the moderator of the Church of Scotland, like they were inviting a martian to the coronation. I’m sure that every major faith community in Britain will have an important role in the coronation. It may be not a big role, but will certainly be acknowledged in a significant way.

If you look through the congregation in 1953, it’s just a sea of white faces. The very few people who are not Caucasian were members of foreign royal families or foreign heads of state. That will, thank goodness, not be the case. But is it enough?

It’s a question I honestly am struggling with. In my love for the history, and my fascination with it, sometimes I wonder if I’m allowing myself to be a little bit bedazzled by all of it and not taking into sufficient consideration the fact that there are problems here. How do we address them?

And is this the moment to address them? Maybe we just take in the coronation and accept it for the historic event that it is. And then in the coming weeks, months, years, we see the king moving to again address these historic inequities.

I think actually [the king] wants to. I think he is someone who is committed to a sense of positive change in a way that his mother, bless her, was not necessarily committed to. Part of her self-discipline, which was formidable, that level of discipline often also goes hand-in-hand with a certain type of inflexibility.

For all that the king is not a perfect person, I think he is able to hear and recognize the need for some change. Is it going to come fast enough for the average person in Britain? I don’t know. Because I think the average person is feeling pretty miserable about the state of things today. And the cost of living crisis is profound.

How to kind of connect with people and make them feel that they belong, that they’re part of these celebrations, that the celebrations are for them, too? It will be the great challenge. I will be fascinated to see how this all unfolds.

Before we close, I want to take a moment to talk about when in your career you started writing books. This chapter in your career is relatively recent, isn’t it?

My first book, Somewhere in France, was published 10 years ago this year. My kids were little, but they weren’t so little that it would have been a real hardship to go off, here and there, for book events. It’s really difficult to keep all those balls in the air when you have little, little ones. Now I call mine “self-watering” at this stage, for the most part. They’re in their late teens and pretty independent. There’s a real freedom to that.

The pressure on people in their teens, 20s, early 30s to figure it all out is crushing. Whenever I talk to young people, if I’m invited to talk at a school, one of the things I wanted to leave these kids with is: Please don’t worry if you haven’t got your life plan sorted out and carved in granite by the time you’re 20 years old.

I did not start writing seriously until I was 37 and I didn’t have my first book published until I was 42, almost 43 in fact. And it’s as it should have been. Everything I did before led to my having the maturity to write these books. And I don’t regret any of it. I think I started writing exactly when I was meant to.

My thanks to Jennifer! You can buy Coronation Year at your local independent bookstore, on Amazon, Bookshop, or wherever you get your books. I also highly recommend The Gown (I know at least one chapter of the SMT Book Club has already picked it for their next read!). Give Jennifer a follow on Instagram, too — she’s @AuthorJenniferRobson.

Speaking of the coronation! My coverage here on Substack officially kicks off later this week. Make sure you are signed up for a paid subscription to receive every newsletter in full, my companion podcast, and the SMT coronation gatherings.

If you cannot afford a paid subscription, please sign up for a free one first and then send me a note at Hello@SoManyThoughts.com.